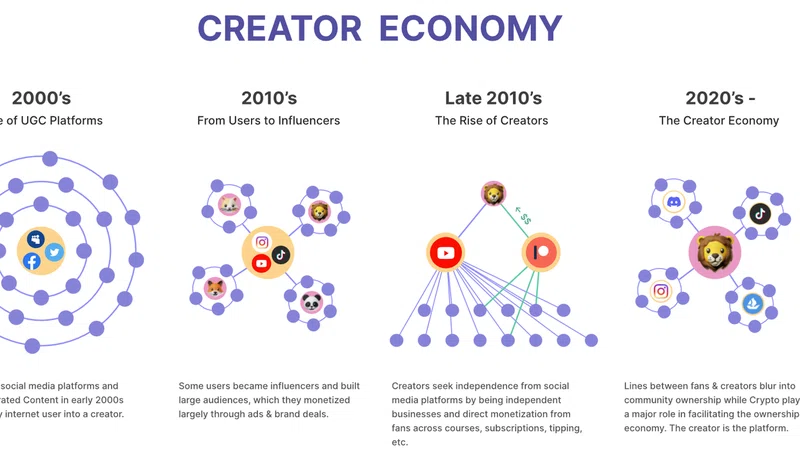

Blockchain — or distributed ledgers more broadly — are perhaps best known for the flurry of cryptocurrencies that have proliferated across the world in the past decade. Yet, despite the buzz, the implications of this new technology have been far from fully explored. As climate risk regulation transforms much of modern finance — with the Securities & Exchange Commission poised to issue new standards as soon as later this month — crypto will likely play a critical role in the climate fight.

Cryptocurrencies are commonly thought of in opposition to emissions targets, but this may not always be the case. Although many are infamous for their energy use, this is an engineering challenge that is far from insurmountable. The enormous — and exponentially growing — environmental footprint of common currencies like Ether and Bitcoin is not intrinsic to all crypto, but specific to proof-of-work. With more investment in developing other consensus mechanisms, like proof-of-stake, the energy footprint of Ethereum and other platforms would plummet.

Arguably, the current debate over blockchain’s climate impacts parallels the divide in the environmental community over the role of AI and even the early Internet. Although once pilloried for their energy footprint, new technologies and their transformative power have been embraced by many advocates. Or, more cynically, many simply realize the impossibility of putting the cat back in the bag. Technologies that once seemed on a collision course with climate targets have been transformed over time into incredible tools for change. From underwater data centers to AI that helps protect the Amazon, other emerging technologies have made enormous strides in bringing both emissions and energy use down. Seeing crypto as a potential climate solution, rather than simply a climate villain, builds on a long legacy of transforming new technologies into environmental allies — or at least actively working to make them less destructive.

The climate finance case for blockchain — from transforming renewable energy finance to saving sharks and other species — has not yet been fully made. Yet, arguably nowhere is blockchain potentially more transformative than in disaster risk. Parametric insurance — an obscure yet surging area of investment around the world — may well be the next major market trend in crypto. But why this sudden interest?

For decades, natural disasters have stretched the limits of conventional insurance. Countries in the South Pacific now pool their national budgets to cover the cost of typhoons that approach their annual GDPs. Adam McKay, the director of Don’t Look Up, recently announced on Twitter that his home insurance had been cancelled due to wildfire risk. As more severe storms buckle and eventually break conventional insurance networks, parametric insurance has increasingly stepped in to fill these gaps. Parametric insurance presents many pitfalls — and, despite recent efforts by the Commodity Future Trading Commission (CFTC), it remains largely unregulated. But, for people whom other insurance companies now refuse to cover, what other choice is there?

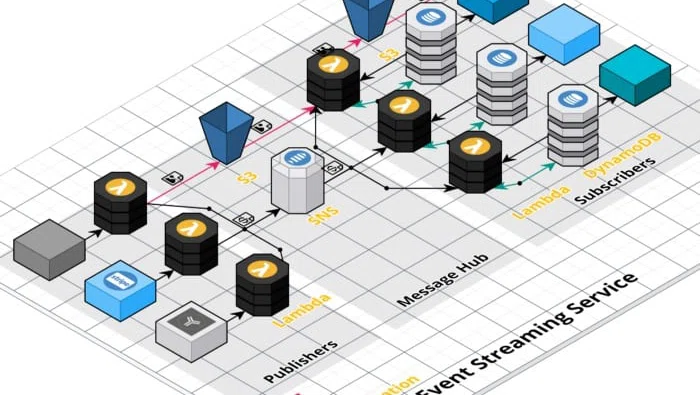

Parametric insurance is, in the view of the CFTC and many other finance experts, actually not insurance at all, but a form of futures, or swap contracts, similar to other derivatives. Smart contracts, often built on platforms like ChainLink, automatically trigger payment when a specific parameter or condition is reached. This “parametric” part is what makes this form of insurance fundamentally different — rather than waiting days, weeks, or even longer for a claims adjustor or FEMA official to inspect storm damage, payment is instantaneous. As soon as a hurricane reaches Category 5, parametric insurance can provide life-saving assistance to people on shore — potentially even before the storm makes landfall. The pre-negotiated cost of a storm of this scale is what triggers payment, not subjective standards after the fact.

Parametric insurance closely parallels weather derivatives, which have been used for years by some of the world’s biggest banks to hedge against adverse events like their offices flooding in New York and other coastal cities. Yet, despite being around for decades, before blockchain such contracts remained largely in the rarified world of Wall Street derivatives desks. Many are concerned by what introducing complex financial products like swaps to retail customers might mean. Will desperate people in the path of fires or floods read the fine print, or fully understand what they’re signing up for? Will parametric insurance in the Global South, as overseen by the World Bank, parallel past patterns of colonial exploitation, and crushing colonial debt? While it is true that parametric insurance presents many new challenges, arguably the greatest risk of all is to do nothing.

Disaster recovery in America — and indeed across the world — is profoundly unjust. Each year, an estimated 26 million people globally are pushed into poverty by natural disasters. Women, who often lack access to credit and conventional finance, are an estimated 80% (or perhaps even more) of climate refugees. The largest civil rights lawsuit in American history, Pigford v. Glickman — the settlement of which has still not been fully paid — was in part due to USDA’s refusal to allow Black farmers access to disaster relief after their crops flooded. This is a pattern that has continued across time. From FEMA’s longstanding refusal to recognize heir’s property deeds, which locked many Black families out of disaster relief entirely, to persistent racial bias in how relief is assessed, disaster insurance in America and much of the world has never really managed to reach those most at risk.

By flipping much of what we know about insurance on its head, smart contracts built on blockchain could help combat inequalities centuries in the making. What if, instead of relying on property values rooted in redlining, we set an objective, equal standard for how much it costs to recover from a storm? What if we let people negotiate that number directly, before the storm hit? What if we made the tools to build those contracts more accessible than ever before, so more people could have a say in designing them than ever before? These are just a few of the possibilities that were almost unthinkable before blockchain removed parametric insurance from the rarified world of weather derivatives, and made it radically more available. From the FinTech sandboxes of Fiji to ChainLink and other platforms, parametric insurance is more accessible, arguably, than many conventional insurance providers have ever been.

As interest in the promise of parametric insurance rises, there are still, of course, tremendous risks. Especially as so many financial systems around the world struggle with how to govern crypto, legal protections for customers have a long way to catch up. But, despite some of the dangers of emerging climate finance products in the crypto space, arguably the most dangerous choice is not to engage at all. Much of the governance framework and building blocks of crypto climate tech remain to be written. Disaster risk affects all of us — and all of us can be part of the solution.