Originally created for the digital cryptocurrency Bitcoin, blockchain technology has since been applied to a variety of use cases.

At FundApps, we’re interested in exploring a use case applied to financial reporting. Our flagship product enables our clients to meet a global regulation called Shareholding Disclosure. This requires significant shareholders in companies (both long and short holdings) to disclose positions to the market, assuring transparency in what companies are held and by who.

We’re curious about the potential of blockchain when applied within the Regulatory Technology space. What would happen if every company (issuer of shares) operated using — like Bitcoin — its own blockchain; that is, a decentralised, publicly accessible ledger? Could this technology be useful? What could it achieve? Let’s consider an example.

On IPO, XYZ Corporation issues a set number of shares for sale linked to its LEI (Legal Entity Identifier).

The number of shares and the distribution of shares bought by the public or institutional investors is recorded in a blockchain ledger.

On day one, XYZ Corp has:

- All shares in issue recorded on the blockchain, where one block will represent one share.

- Every transaction in the IPO recorded on the blockchain.

- Every company (represented by their wallet address, shielding their company identity) who purchases shares and their holding of the issuer’s shares recorded on the blockchain.

Investor Identity

The bitcoin protocol uses a private and public key system where a wallet address is used as an identifier. The private key is used to prove ownership of the public key and allows access to the funds associated with the public key. This key system obscures the identity of the account holder but not the transaction.

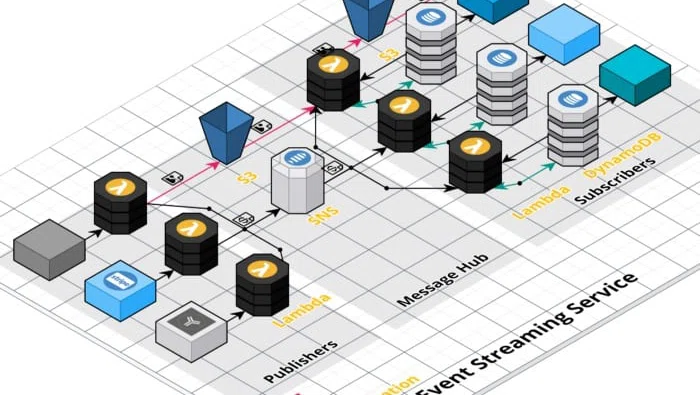

At a basic level, the blockchain functions as a public list which stores a permanent and publicly accessible history of all transactions to ever occur in the history of Bitcoin, or, for our purposes, XYZ Corp. It is an append-only ledger, meaning that any information added to the ledger cannot be deleted. These characteristics ensure immutability as well as transparency.

Using a wallet with a private and public key encryption system, investors could trade XYZ Corp in relative privacy. Their transactions on the blockchain would be linked to this visible wallet address but would not be linked to their company. All trading activity of XYZ Corp assets would be recorded and then, subsequently, all disclosures automated. For example, by creating a smart contract which states that when an investor’s holdings exceeds, for example, 5% of the issued shares, that investor and their transaction must be made public or flagged to the relevant regulator.

This raises issues of verifying investor identity, as wallets provide a mostly anonymous interaction with the blockchain. An alternative solution would be XYZ Corp offering a permissioned blockchain, where the blockchain has functionality to verify participants and limit what they can see and input.

Transactions

What implications does this have for the buying and selling of physical shares in our IPO’d XYZ Corp?

The transacting of shares would be recorded on the blockchain. All transactions and relative ownership in the company would be automatically updated. If XYZ Corp wanted to buy back shares and hold them in treasury, this would be recorded on the blockchain. The holder of the shares then would be identifiable as XYZ Corp, the issuer.

There would be a dramatic impact on the regulation workflow for the shareholders, as well as regulatory requirements. In theory, because blockchain records cannot be modified once created, there would be a decreased need for regulation in the traditional sense. There would be one source where shares could be bought and sold. They would be recorded immutably in a shared and publicly accessible network, and verified regularly by the network. Regulation would be made easy, automatic and hypothetically, fraud-proof.

The role of a broker would also be dynamically altered. Could anyone be granted access to buy and sell on the blockchain? Whilst the days of physically trading shares have been reduced by the rise of electronic trading, could blockchain render the pit obsolete entirely? What then are the implications for exchanges?

Derivatives

Let’s say Fund Zero and Fund One want to trade a cash settled OTC Swap on XYZ Corp. This is a financial contract that traditionally would occur without using a public exchange and in this context, would be struck outside of the blockchain. Fund Zero and Fund One, however, would still have exposure to the underlying issuer, XYZ Corp, and need to adhere to regulatory requirements.

As described, a smart contract functions as an automated intermediary. The program could validate the transaction, record it on the blockchain and enable the transfer of funds between the parties’ banks. Whilst OTC transactions and derivative contracts would occur outside of the blockchain, they would still be managed by and recorded within it. This process could also be applied to short selling.

Suddenly, holders are able to monitor cash and physical exposure to XYZ Corp. The blockchain provides an accessible, immutable audit trail. Not only that, but the transaction costs associated with physical trading created by third-parties is reduced; all middlemen are replaced by the blockchain.

Additional Issuances

At times, tracking corporate actions can be challenging for Investment Managers. It is typically a manual process of being alerted of an event happening (e.g a stock split, or rights issuance) and then reading of the outcome. Data providers then may update relevant company information immediately, or this can be delayed. By storing company share information in the blockchain, this could allow issuers to directly update information there, thus automating updates directly back to the investors and automating something that currently is slow and manual.

Is this a good idea?

Blockchain technology within a Regulatory space offers impressive benefits around transparency and immutability.

Transactions are automatically recorded and verified by the network, removing the need for holders to manually disclose. Because the blockchain cannot be modified once saved, regulators could use it as an audit trail. Users have full autonomy, and trading could be streamlined as a result without the interference of often expensive intermediaries. Furthermore, the public blockchain structure explored here offers the highest level of security, theoretically reducing the risk of fraudulent activity.

Why isn’t this a good idea?

Blockchain technology isn’t infallible. In reality, public blockchains are slow. This would present a risk for investors due to time pressured disclosure windows, and would not perform well in a reactive, fast-paced trading environment.

Shares would never be physically owned; they would be represented by some form of asset-backed token on the blockchain. This presents opportunities for fraudulent activity and issues around proof of ownership. Questions emerge around regulation of the blockchain itself, what token would be used and how they would map to fiat currencies. Adoption for existing companies would necessitate a technology overhaul which presents skill and cost challenges. There’s a question of whether companies would be able to access or fund the resources required to integrate, create or support a blockchain system.

A mostly anonymous platform like the one proposed here could — as has happened in the cryptocurrency space — attract malicious behaviour. There are questions for financial institutions, then, around risks; security hacks, operational issues and who is responsible for regulating them, to name a few.

Fraudulent activity such as illegal market manipulation is facilitated by the relative anonymity of blockchain platforms. For example, from a regulator’s perspective, investors who represent a legal entity have a responsibility to disclose. A legal entity may own several wallets and be represented by multiple addresses on the blockchain. In order to prevent fraudulent activity from multiple wallets representing the same legal entity, there would need to be a manual intervention in place or a permissioned rather than public blockchain to authenticate and consolidate the investor with their wallet to the regulator. This would make automated disclosure all but impossible, negating a key benefit outlined above.

Bottom Line

There are compelling arguments for how blockchain technology could shape and innovate in the financial reporting space. The benefits of increased transparency and immutability within financial reporting are undeniable.

Current restraints suggest that widespread adoption and integration of the technology for this purpose would be difficult, in addition to challenges around preventing fraudulent activity. It’s not a low cost solution, requiring significant investment in more ways than one.

At FundApps, we’re excited by emergent technology and are always looking to experiment and improve existing ways of doing things. We recognise that the present challenges don’t necessarily translate to the future: blockchain has potential to create widespread impact once it has evolved to account for the risks.

This is cross-posted from a blog post I co-wrote with Ben Richards. We’re Product Managers at FundApps, a regulatory technology start-up.