Acorns Grow Inc., the financial technology and investing startup, said that it was abandoning its $2.2 billion merger with SPAC Pioneer Merger Corp., putting itself on the hook for a $17.5 million termination fee. Coming almost eight months after the deal was first announced, the news surprised many in the fintech and SPAC worlds. It shouldn’t have.

SPACs — a method of going public touted as faster, simpler, and cheaper than a traditional IPO — are proving to be a severely flawed way to finance fintechs and other technology companies. Their stock prices have almost invariably declined sharply after merging with their targets, they have been subject to increasing regulatory scrutiny, and while their structural mechanisms worked well in a rising stock market, they have faltered badly in a market turning down.. No wonder Acorns decided to bail.

There are at least five related reasons why SPACs have so spectacularly failed fintechs.

1) Relationship between time and mispricing

It takes too long — from three to more than seven months — between the time a SPAC sponsor and its target company structure, price, and announce their merger deal (at the traditional $10 per share) and the time the merger closes and the merged company’s common stock starts trading. Preparation of a merger proxy statement and accompanying financial statements takes time, as does SEC review and negotiation of requested disclosure changes and the solicitation of shareholder votes. The process has gotten even more complicated and time consuming since 2021, when the SEC first identified serious SPAC accounting issues and intensified its review of SPAC merger transactions.

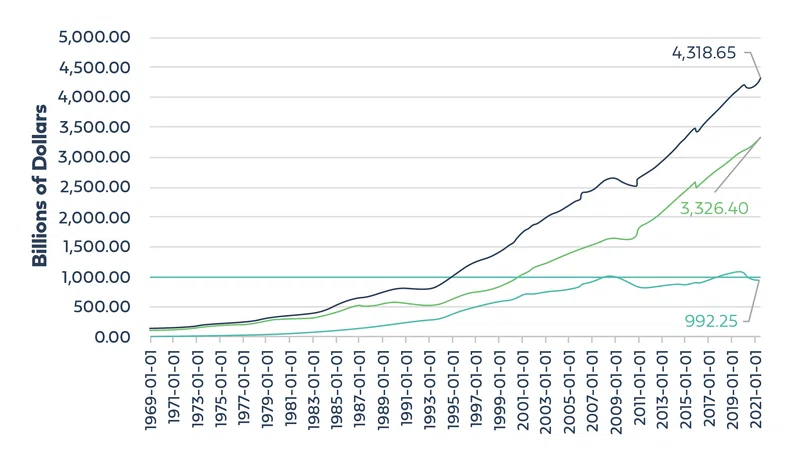

The delay between announcement and closing of SPAC mergers means that the chance of mispricing a SPAC merger is very high, even in moderately volatile markets. A lot can happen in public equity markets over six months to change pricing expectations, as market conditions, sector preferences, and economic outlooks shift. By contrast, in the typical IPO process, deal pricing is the subject of intense, real-time, market-based negotiation with underwriters that possess the most up-to-date information on buyer demand and the target company’s situation and prospects. The high likelihood that any fintech or other SPAC deal will be mispriced — a fundamental structural weakness of the SPAC approach — has been obscured by the recent “goldilocks” equity market. As long as public trading prices for fintechs were rising steadily or were relatively stable, time delays were either beneficial or at worst immaterial. But the potential harm of premature pricing always existed, poised to wreak havoc when the markets shifted and public-market trading prices for fintechs — particularly SPAC-based fintechs — started a steep decline. According to the Wall Street Journal, the stock prices of at least half of the companies that completed SPAC deals in the last two years plummeted 40 percent or more post-merger. Well known fintech SPACs like MoneyLion, OppFi, Paya, and Payoneer were trading at between 26 percent and 60 percent of their $10 per share valuation target at the time of this writing. The only real outlier is SoFi, trading at around $12.75 following the approval by the OCC of its bank charter plans.

2) The redemption incentive built into their structures

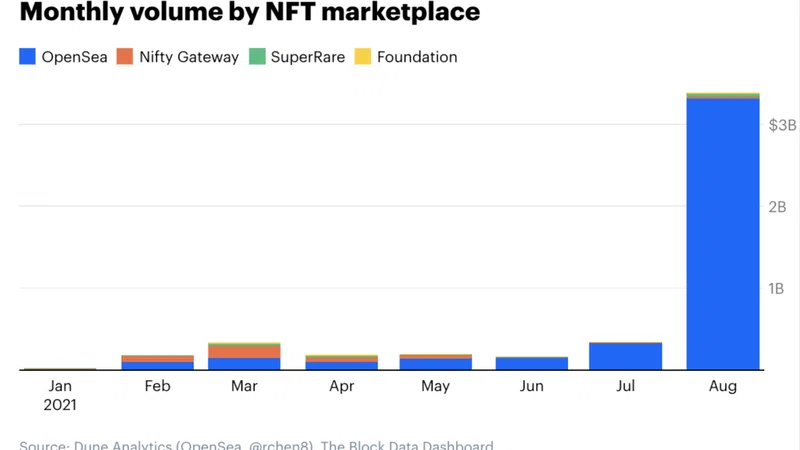

SPACs are “blind pool” investments, and IPO investors have only a general idea of what type of company will merge with the SPAC vehicle. That’s why the investors are allowed to sell their investment back to the SPAC after a merger is announced, typically at the $10 IPO price, plus nominal interest. With recent downturns in the market, many investors in SPAC mergers priced months ago are availing themselves of the investor redemption mechanism. According to the law firm Goodwin Procter, redemptions averaged 60 percent in the last quarter of 2021, with redemption levels exceeding 50 percent in more than two-thirds of SPAC mergers and 90 percent in one of every 10 transactions. Just a few days ago, shortly after completing its merger with hospitality company Sonder, SPAC Gores Metropoulos II disclosed that stockholders redeemed 96% of the SPAC’s outstanding shares ahead of the vote.

Even if an investor really likes the merger partner’s business, redemption is an obvious and entirely logical tactic and an inevitable outcome of the SPAC structure in a falling market. Who wouldn’t sell a stock at $10 to buy it back at $5 in a couple of days?

3) High redemptions nearly guarantee a capital-raising shortfall

The third reason for SPAC failings is a consequence of the second. When a large number of investors redeem their IPO investments, the merger target receives far less in common-equity capital from the IPO than was originally expected. That amount may not be enough for the target company’s business plan, even with the private PIPE financing that typically accompanies the announcement of the merger and, in some deals, the backstop arrangements funded by the SPAC sponsor or an outside investor to make up part of the shortfall. In the Gores Metropoulos II case, only $16.5 million remained in the SPAC trust at closing from the $450 million raised in its January 2021 IPO (Gores and investors chipped in another $110 million to ensure that the deal closed.)

4) Disparity between public and private market valuations

The fourth reason — and the one usually behind cancellation of announced SPAC mergers like Acorns’ — is that the disparity between public and private market valuations for fintech companies gives SPAC fintech partners a financing alternative. Private venture capital and growth equity money is still readily available for fintechs, and at higher valuations than public alternatives. According to Crunchbase, $134 billion in venture money was invested in financial services in 2021, a 177 percent year-over-year increase. Startup valuations have been sharply outpacing public equity indices. Investors have been particularly generous to fintechs, whose valuations increased 2.4 times over venture financings through the third quarter of 2021.

This makes spurning a SPAC easy for fintechs that have access to alternative private funding, which is quicker and less risky than raising money through a public offering and avoids the disclosure obligations and other headaches of being a public company. History teaches that at some point private and public market valuations will converge, but until then, companies grab the best fundraising deal they can while keeping one eye on a traditional IPO or merger or sale a few years later.

5) A negative reinforcement loop that creates continuing problems for fintechs contemplating a SPAC merger

The high-value private-funding avenue is generally available only to fintechs whose top-line customer growth and unit operating metrics are strong. That leaves only relatively weaker companies without attractive private alternatives — even in an overheated venture capital environment — as potential targets for SPAC sponsors. If these companies turn to SPAC mergers as a last resort, that can only reinforce negative perceptions, causing SPAC stocks to trade down even more sharply post-merger and leading even more IPO investors to take advantage of the redemption mechanism. This in turn makes PIPE financing scarcer and more expensive, while placing intense financial pressure on SPAC sponsors that must often make financial concessions to complete transactions.

All in all, it’s not a happy story, and no one should be surprised that Acorns Grow was willing to spend millions in breakup fees to ditch its SPAC merger. It may be joined in future months by more fintech companies that have access to private funding and conclude that it is better to use private money to grow than to brave the stormy and uncertain seas of the SPAC process.

This post originally appeared on January 26, 2022 in the Blue Sky Blog at Columbia Law School.